No products in the cart.

Essays + Dissertations

Routledge Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Literature, THE FEMINIST ARCHITECTURE OF POSTMODERN ANTI-TALES, Kendra Reynolds

Daniela Meneghelli, Brazil, Master’s Essay, 2020 : Subject Dina Goldstein’s Fallen Princesses

Satire and Gods of Suburbia

Text by Charlene Sayo, 2016

Aside from fuelling the already fiery debates surrounding religion, last month’s Charlie Hebdo shootings ignited the polemics of satire as ammunition against religious fundamentalists and marginalized communities most associated with—at least according to Fox News and its ilk—religious extremists. Satirizing religious and political affairs must be done, not only to deepen social consciousness and inspire action, but to reach out to those not easily swayed by abstruse theory and rhetoric. But is it possible to satirize religion and push boundaries without triggering murder?

In immediate response to the shootings, American writer and photographer Teju Cole suggests in his essay, Unmournable Bodies, that “it is possible to defend the right to obscene and racist speech without promoting or sponsoring the content of that speech. It is possible to approve of sacrilege without endorsing racism. And it is possible to consider Islamophobia immoral without wishing it illegal.”(1)

In her latest photographic collection, Gods of Suburbia, Vancouver-based, internationally award-winning photographer and cultural critic Dina Goldstein captures the essence of satire through discussion and criticism about religion, its place and perseverance in our technology-manic society. She knocks off Western and Eastern Gods, deities and icons from their altars and re-imagines them as ordinary people struggling with unemployment, homelessness, identity crisis and alienation. We see Lakshmi attempting to “lean in” with the cumbersome demands of domestic responsibilities and public life. For his last supper, Jesus feasts with hipsters in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside observing the conflict between homelessness and gentrification; and a riff-raff Wiccan couple, models for many pop-up fringe spiritual communities, are construed as being so awkward and estranged, they are, according to Goldstein, “living on the outside of the mainstream, along the periphery of Suburbia.”

By re-imagining Gods and deities as fallible creatures unworthy of worship, Gods of Suburbia dares to ask: Is religion a commodity akin to a sparkly iPhone that can upgraded, traded in, or disposed for the latest model? How can the practice of religion, so private and personal, be so public? How has religion been able to thrive in our science-driven, secular society?

By constructing a cosmetic reality, one that mirrors our own, Goldstein doesn’t evade discussion, but rather creates it. In doing so, Gods and deities, believed to be too sacred for criticism, are personified and whose religious practices contradict their dogma.

This plastic aesthetic within Gods of Suburbia reflects our manufactured, consumer world, where religious idols are not only out of place, but are actively being displaced. In fact, there is a sadness in the photos, because without their shrines and shiny halos, the icons are comparable to plastic flowers and bejewelled sunglasses sold in dollar stores—the meccas of consumer overproduction and excess. Goldstein’s Buddha exemplifies the commodification of religion, by way of exorbitant prayer beads and eat-pray-love five star retreats. “I’ve placed Buddha in a high-end supermarket to illustrate how far we live and exist from the ideals of Buddhism, which we in the West pay homage to with Yoga and meditation,” Goldstein explains. “The irony is that we continue our immersion in the three poisons when we shop at such overpriced designer supermarkets. […] They indulge our narcissism and desire—separating the haves even further from the have-nots, who can’t shop at such places and are left with GMO and lower-scale food.”

This consumerism reveals on the one hand, religion’s vulnerability to commodification, and, on the other, its ability to navigate our consumer cosmos, adapting to rapid changing consumer wants and constructed needs. In doing so, this reveals our active role in the commodification and the demonization of religious beliefs.

The striking difference between the Charlie Hebdo illustrations and Gods of Suburbia is, despite Goldstein’s critique on religion, she remains respectful to the Gods and deities by rooting satire and contemporary narratives within the axiom of their history and spirituality, therefore enhancing, rather than distorting the essence of religious icons. Muhammad the Prophet is exalted as Goldstein recognizes Islam’s contribution to the sciences long before their European counterparts, juxtaposing “the obvious disconnect between the East, specifically Islamic principles and the West’s secular ideals, which is currently at the forefront of international concern.” Ganesha, the Lord of Obstacles is depicted as a tormented outsider struggling to integrate in a hostile world, an experience Goldstein felt “as an immigrant to Canada [.] I was bullied for being different and for not speaking English—you can see in the photo that what differentiates people is not only what they eat, and how they dress, but also what they believe in.” There is a universality within the alternate world of Gods of Suburbia that many of us can relate to. The Charlie Hebdo illustrations on the other hand, depicts marginalized communities, such as France’s 4 million Muslims under the lens of racist stereotypes so detached not only from their religious and spiritual roots, but also alienated from the strained colonial history between France and its former colonies. The illustrations did not contain Islamophobia, but in fact, incited Islamophobia, and consequently, its backlash.

If done right, satire can enlighten; if done carelessly, satire can lead to violence as our world has witnessed over again. To not understand this dynamic is irresponsible on the part of the artist. Satire must be clever, and like many cultural forms, must encourage the awareness and potential intellect of all members of society, religious or not. At its best, satire not only critiques social values and norms, but provokes change if necessary, positioning individuals to be active participants in social transformation, rather than passive consumers who allow others to worry about their civil liberties and freedom.

The filtered, plastic universe of Gods of Suburbia points the finger at all of us and our inconsistency to uphold spiritual peace within our manic, individualistic consumer world. In the end, Goldstein’s work not only exemplifies satire, but she has created an alternative space where Gods can live among us, but only in so far that we can see our faulty selves in this made-up reality.

[1] Cole, Teju. “Unmournable Bodies.” The New Yorker, 9 January, 2015. Web. 22 January 2015. <http://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/unmournable-bodies>

Dina Goldstein’s In The Dollhouse and the Perils of Plastic Perfection, 2016

Since her 1959 debut wearing stilettos and a zebra print bikini to the tagline, “a shapely teenage fashion model” and theme song Barbie You’re Beautiful, Barbara Millicent Roberts has been a lightning rod for debate about the socio-cultural expectations for female identity. She certainly looked different from the typical baby-faced dolls of her day. Tall, thin, golden-haired and glossily made up, Barbie was modeled after Lilli, a curvy sexualised doll sold in German bars to adult men based on a racy comic strip character. Equally as buxom, Barbie expressed her personality through her body image, wardrobe and lifestyle. Acquisitive and carefree, Barbie is the glamour girl of a mythic America where being perfect, popular and plastic is the highest ideal. As a corporate-sponsored American princess, Barbie was made to live the dream of a good life.

That’s not Barbie’s fate in Dina Goldstein’s hands.

For her second conceptual series of large-format photographic tableaus, Goldstein subverts the storybook storyline of Barbie and her blow-dried boyfriend Ken. Using the sequential narrative form common to comic books, Goldstein places the long-time couple in a custom-manufactured alternative reality of her own design and decoration. A pink on pink playhouse that seems sweetly perfumed for romance. Even the pillows insist on love. But the candy-coloured interiors and playful appeal of the iconic dolls are Goldstein’s Pop Surrealist lure to engage an audience about serious issues. In The Dollhouse is social documentary photography masquerading as a puppet show. The series of 10 panels unfolds a tragicomic tale of the perils of being plastic and the potential for salvation through authenticity. Barbie gets the short end of that stick – in Goldstein’s telling of her story, she endures psychological dysfunction, an emotional breakdown, a really bad haircut and, ultimately, decapitation.

Life wasn’t supposed to be this hard for Barbie.

Shaped into Barbie’s form – and all her fabulous clothes – is the cultural expectation that her life is charmed. She is the ultimate material girl meant to have it all – iconic beauty, gravity-defying breasts, salon-perfect hair, wafer-thin waistline, any job that she wants and a boyfriend content to live in her shadow for more than 50 years. From her proportions to her wardrobe, Barbie sets an impossible standard for girls and the grown women they become. With over a billion sold and the average girl owning at least 8 Barbies, developmental psychologists indicate the dolls plays an active role in shaping a young girl’s self-image. Arguably, Barbie’s a tool in the hand teaching females that appearance and material possessions matter for achieving social status. And, possibly, a gateway drug to a lifelong obsession over what it takes to fit the ideal of feminine beauty.

Dina Goldstein’s photography projects have made her an iconoclast in fantasyland. Her acclaimed series Fallen Princessesrecontextualized Disnified heroines to engage awareness about societal challenges: pollution, war, obesity, marital dysfunction. As with In The Dollhouse, Goldstein draws from her earlier photodocumentary work and her keen ability to find the fragmented truth in a story no matter the scene. Goldstein’s scenes are no longer happened upon but diligently arranged though the artifice is still meant to be cut from the coarse cloth of social reality. As a surrealist, Goldstein knows that beneath the smooth, polished surface of our pop cultural age, the truth is writhing to be set free. Her work is intended to – and does – provoke debate. It’s intentionally theatrical but has an honest message. Every image is queerly compelling.

Still, the comedy and charm of In The Dollhouse can’t be denied. Goldstein has set an immaculate scene and found the cast to match it. There is an overlay of 1950s ornamentation and respectability in the setting: the French Provincial furniture package, fine china tea service, Barbie’s well-coiffed hair and taffeta dress, Ken’s sweater dashed about his shoulders. Everything is in its proper order – well, almost.

Bored and oblivious, Barbie is about to have her perfect life tripped up by the bold gay kick of Ken’s pink pump. If Oprah didn’t give away his secret, the bleached-out dude doll just getting out of bed with Ken definitely subverts the couple’s corporate marketing story. Admittedly, Ken has always been subject to rumours. When Mattel issued Magic Earring Ken in 1993 – complete with buff body, mesh tanktop, mauve vest and a much speculated upon chrome ring about his neck – the doll sparked controversy and was soon discontinued and recalled despite its popularity. Twenty years on, in Goldstein’s fantasia, Ken is more carefree and happy to lead his life as he chooses. It’s Barbie who struggles with her identity. As the power of her synthetic perfection proves worthless, Barbie ends up broken in the corner. Just another doll, headless and forgotten.

The final panel of In The Dollhouse is shocking but the penultimate one more sensitively links Goldstein’s artistic efforts to a bigger purpose. The socially-constructed expression of female identity, beauty and individuality is, of course, much older than ageless Barbie. In The Dollhouse contains a bonding moment with Frida Kahlo, the Mexican artist known for her fierce and wounded self-portraits – as well as her tempestuous relationship with the frequently unfaithful Diego Rivera. Kahlo endured great pain throughout her life, both physical and emotional, and poured that hurt and heartache into her paintings. Watched by a voyeuristic eye peering through the back window, Goldstein’s The Haircut recreates Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair – both women pictured are shorn of their long locks and wearing a man’s suit. The visual conversation between these two provocative female artists – creative girl talk – is raw and poignant and sly. The “proper” role of women in society and how to fit their frame to that prescribed form becomes for Goldstein, as much as Kahlo, the motivation for her metaphorically surreal imagery. Goldstein shows the price that women pay trying to be perfect.

A relational postscript to In The Dollhouse is the real life hardships endured by the people who made or inspired Barbie and Ken. Ruth Handler, the Mattel President who came up with the idea for Barbie, was diagnosed in the 1970s with breast cancer and underwent a radical mastectomy. Jack Ryan, the chief engineer who shaped the look of Barbie, was a six-times married hypersexual swinger known for hosting wild orgies in his lavish Bel Air home; he suffered from alcoholism and took his own life in 1994 (writing “I love you” on the bathroom mirror using his last wife’s lipstick). The real life Ken, son of Ruth Handler, hated being associated with his namesake doll; though married, he was a closeted gay man and died in 1994 from an AIDS-related complication. Barbara Handler, or Barbie, also shuns the association; after her divorce and various cosmetic surgeries, she lives as a recluse in Southern California.

Such are the truths of regular life. Nothing is plastic coated. The human condition existing in the real world is complicated and lacks the fantastical powers required to make a life perfect. Still, there can be beauty despite the flaws. In Goldstein’s visual narrative, Ken embraces his particular kinks and is liberated. Barbie – stubbornly and stylishly conservative – is destroyed. But maybe the scene in Goldstein’s last panel is transitional, not final. Dolls are resilient. They can take a beating and then snap their heads back on and begin the game again.

Goldstein’s In The Dollhouse plays with our narrative expectations as well as our cultural ones. In the toybox of social popularity, can our culture love a Buzzcut Barbie? Who will play with her now?

Subverting the Myth of Happiness: Dina Goldstein’s “Fallen Princesses” Jack Zipes, 2010

Jack David Zipes

An American retired Professor of German at the University of Minnesota who has published and lectured on the subject of fairy tales, their evolution, and their social and political role in civilizing processes. According to Zipes, fairy tales “serve a meaningful social function, not just for compensation but for revelation: the worlds projected by the best of our fairy tales reveal the gaps between truth and falsehood in our immediate society.” His arguments are avowedly based on the critical theory of the Frankfurt School and more recently theories of cultural evolution.

When feminists began -re-writing fairy tales in the 1960s and 1970s, one of their major purposes was to demonstrate that nobody really lives happily ever after, whether in fantasy or reality, and one of the important political assumptions was that nobody will ever live happily ever after unless we change not only fairy-tale writing but social and economic conditions that further exploitative and oppressive relations among the sexes, races, and social classes. This general purpose is still at the root of the best and most serious writing of fairy tales by women, and in recent years, some of the best women painters, artists, photographers, and filmmakers in North America have created unique works that question traditional representations of gender, marriage, work, and social roles.

In order to explain why nobody lives happily ever after, neither in fairy tales nor in real life, and why nobody should invest their time and energy believing in a “happily ever after” realm, I would like to make a few comments about Dina Goldstein’s provocative photographs that pierce the myth of happiness. This is not to say that we cannot be happy in our lives. Rather, I should like to suggest that the fairy-tale notion about happiness must be radically turned on its head if we are to glimpse the myths of happiness perpetuated by the canonical fairy tales and culture industry and to determine what happiness means.

Anyone who has seen Dina Goldstein’s unusual photographs knows that she not only deflowers fairy tales with her tantalizing images, but she also “de-disneyfies” them. Goldstein came to Canada from Israel when she was eight-years-old and had very little experience with the world of Disney films, books, artifacts, and advertisements. It was not until she was much older, when her three-year-old daughter was exposed to the Disney princesses, and when her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer that she began to reflect about the impact of the Disneyfied fairy tales. As she has said in an interview with the Vancouver Sun, “I began to imagine Disney’s perfect princesses juxtaposed with real issues that were affecting women around me, such as illness, cancer, addiction and self-image issues. . . . Disney princesses didn’t have to deal with these issues, and besides we really never followed their life past their youth.”

Goldstein’s photo series, “Fallen Princesses,” first appeared on the Internet in the summer of 2009, and they have received global attention as artworks that comment critically on the Disney world and raise many questions about the lives women are expected to lead and the actual lives that they lead. Her photos are not optimistic. Rather, they are subtle, comic, and grotesque images that undo classical fairy-tale narratives and expose some of the negative results that are rarely discussed in public.

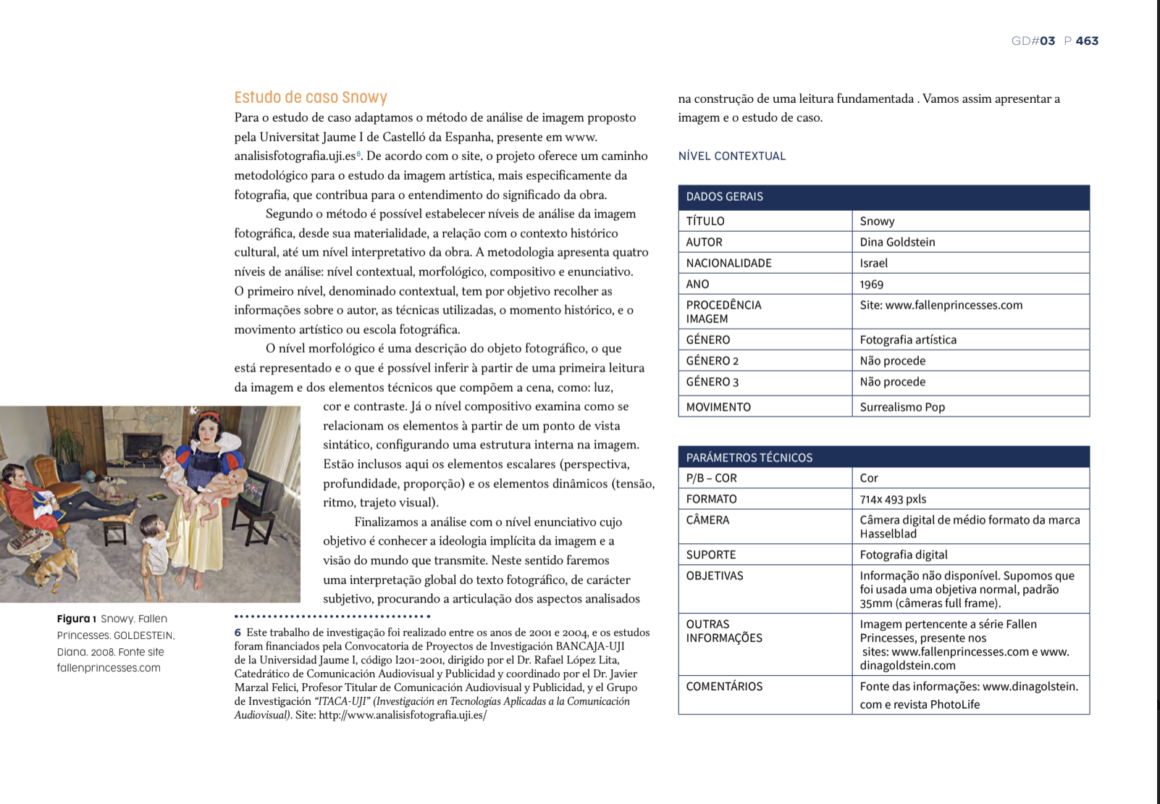

For instance, in her macabre portrayal of Snow White, she depicts the gruesome fate of a young woman, who is the spitting image of Disney’s Barbie heroine. She stands in the middle of a suburban living room holding two of her children in diapers, one crying, one sucking her thumb. Another daughter is pulling on her skirt, while a fourth is crawling in a corner of the room. A tiny bulldog is sniffing the ground. The woman stares solemnly into the camera while her prince-like husband sits on an easy chair and watches a sporting event on television. Of course, he is holding a can of beer and is totally detached from his family. In another photo in the series, Snow White and her prince stare into the camera, completely alienated from one another. Whatever love there was between then has vanished.

Is this what marriage and family life are supposed to be? Goldstein does not generalize, for these are very specific social-class images that may resonate with viewers from all classes in different ways. If anything, Goldstein is concerned with the struggles that women must endure despite the gains made by the feminist movement in the past forty years. Her Rapunzel loses her hair perhaps due to chemotherapy. Her Belle undergoes plastic surgery so she can maintain her status as a beautiful woman. Her Red Riding Hood cannot stop eating and is so obese that the wolf might not be attracted to her, or perhaps he will find her extremely attractive. Pocahontas sits in a daze while watching television in a room stuffed with artifacts of natural life and surrounded by domestic cats. Indeed, Native American life appears to be tamed and domesticated. This is the same with the Little Mermaid, who is encased in an aquarium and has become little more than a display object. While not on display, the princess on top of the mattresses in a dump yard does not fare much better. She will not be awarded a prince after sleeping on a pea. Instead, she is about to be swept away and discarded by a bulldozer. And perhaps this is a good thing because the pea test she was expected to pass is a patriarchal myth of the past and belongs to the refuse of history.

Goldstein’s scenes are carefully and artificially arranged, and yet, they do not seem posed. They are mock portraits of posed family scenes and sardonic cuts of fairy- tale films. They assume a life of their own because they are livid studies of depressing situations that need to be faced, not averted. The princesses in her photos are fallen because they had fallen for the Disney images and societal norms that are perverse or destructive for women. (Not to mention men.) They cut to the core of alienation and banality in our glitzy lives. This does not mean that there is no happiness after the happy ends of classical fairy tales, but her photos imply that women (and men as well) must be on the alert in the society of the spectacle not to believe the images imposed on us, but to create our own narratives and representations. Goldstein has boldly and fascinatingly exposed the underbelly of daily life in her photos. The fallen princesses in her photos — her representations — emanate from a critical vision and artistic endeavor that seek to come to terms with social conditions that limit our ability to recognize the myths of happiness. By picturing the consequences of manipulated fairy tales Goldstein hopes that we may alter our vision and contend with the spectacles in life that blind us with dazzling false promises.

Li Cornfeld

PhD Student at McGill University

Shooting Heroines: The Promise of Enchantment in Dina Goldstein’s Fallen Princesses

In the spring of 2011, the Catherine Hardwicke Red Riding Hood movie made a hard play for the tweeniebopper Twighlight demographic, even as Cinderella Ate My Daughter, Peg

gy Orenstien’s critical examination of preschool princess culture, climbed the New York Times bestseller list. From the pink tiaras and sparkly wands coveted four-year-olds, to the teen and tween fixation with sexy wolves and vampires, the motifs of enchantment dominate contemporary girlhood as strongly as they ever have. In his seminal work The Uses of Enchantment, psychoanalyst Bruno Bettleheim outlines the ways in which fairy tales provide children with a foundation for emotionally healthy adulthoods. The fantastic, magical struggles experienced by otherwise normal fairy tale characters, writes Bettleheim, prepare children to appropriately acknowledge and address the harrowing emotional ventures which accompany psychological maturation, while unfailingly happy endings teach children to trust in the possibility of successful futures (Bettleheim 1975).

What happens, we might ask, when real life happy endings fail to deliver the enchanted promises of fairytales? Photographer Dina Goldstein’s Fallen Princesses, a series itself inspired by her three-year-old daughter’s obsession with Disney princesses, uses the visual vocabulary of fairytales to emphasize decidedly mundane, un-magical realities faced by contemporary women. If, as Bettleheim argues, folkloric enchantment provides children effective tools for negotiating their futures, Goldstein’s series suggests an enduring power that the promise of enchantment holds for adults, even (or especially) adults who suspect enchantment of falsity.

Enchantment Lost

The ten-photograph series uses a bright, painterly palate to depict grown women dressed as fairytale heroines in contemporary scenarios, juxtaposing enchanted beginnings with mundane realities. Snowy, the first image of the series, transforms a Disneyfied Snow White into an overburdened housewife. With black bobbed hair and dressed in the iconic gown of Disney’s primordial princess, Goldstein’s Snow White stares numbly into the camera, a baby in each arm, a toddler at her skirt, and a third child crawling in the background. Prince Charming lounges in an armchair, stockinged feet up on an ottoman, watching TV and drinking beer. If the visual joke is easy, it is also provocative and dense.

Snow White can, and has, been subjected to a wide variety of readings. Bettleheim, for his part, sees the tale as an oedipal drama which pits mothers and daughter’s against one another in competition for patriarchal love (Bettleheim 1975). Significantly to Goldstein’s narrative, however, nearly every reading of the tale interprets Snow White as a conventional coming of age story. As such, the tale follows its titular hero’s journey through adolescence; the bulk of the tale takes place in between the kingdoms of her childhood and adulthood. In the woods, a space suggestive of growth, she practices a preparatory domesticity for miniature men until she reaches a sort of stasis, which occurs when she ingests a maliciously enchanted apple brought to her by her competitive stepmother. Tellingly, the Grimm narrative ends not with Disney’s kiss, but with the prince carrying a comatose Snow White into his kingdom; it is upon leaving the woods en route to a new space that she emerges as an adult capable of standing on her own two feet. Later, at her wedding to the prince, her stepmother is forced to wear hot-iron shoes, which literally cause the old queen to go up in smoke. Obsession with staying young, the story seems to say, results in fast burnout; better to grow old with Snow White’s grace.

Snow White is thus is a fitting introduction to Fallen Princesses, a series which addresses elements of aging in the context of fairytale enchantment. The complaint issued by Snowy, of overburdened mothers with disinterested husbands, interrogates the relevancy of an enchanted adolescence to a suburban, domestic adulthood. If the Grimm’s tale condemns the Queen for her attempts at staying a youthful beauty, Snowy’s dull reality renders the opportunity to be an old woman in killer red hot heels an appealing option.

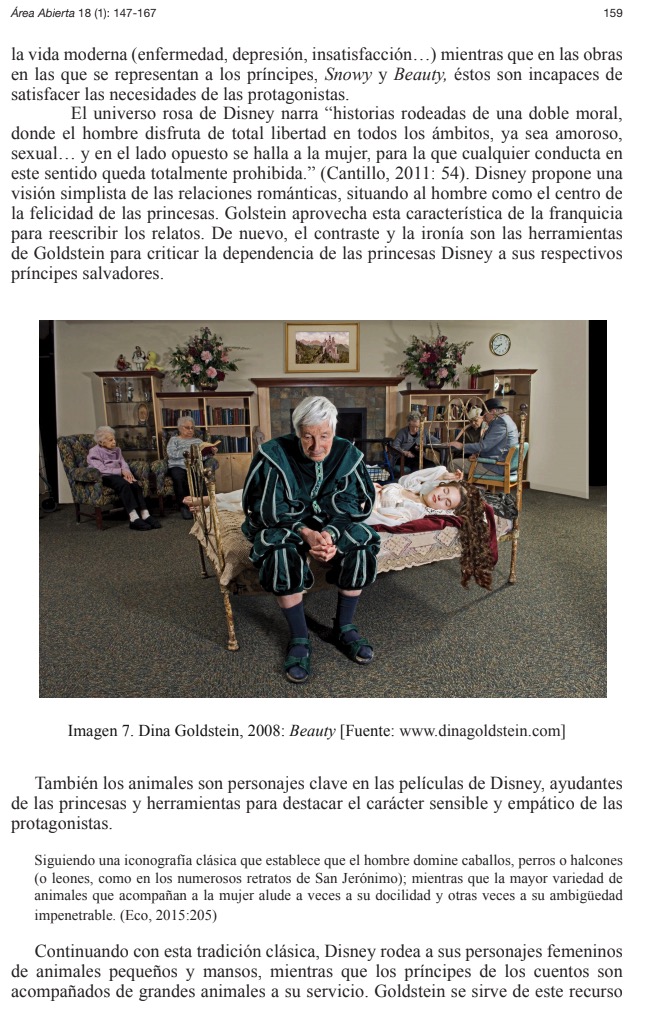

Yet while Fallen Princesses addresses the role that enchantment plays (or ceases to play) as women grow older, its depictions of older women trying, like the wicked queen, to maintain their youthful image is literally not a pretty picture. In the photograph Belle, a woman with red lips and carefully sculpted eyebrows, dressed in the gold ball gown of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, undergoes grotesque plastic surgery. In Beauty, the Prince of Sleeping Beauty rests on a bed in a retirement home recreation room beside his still-youthful bride, young but comatose. If fairytales routinely address adolescent girlhood and early marriage, Fallen Princesses uses tales whose core themes include the enchanting, transformative power of beauty to emphasize the sometimes paradoxical construct that is growing old with grace.

Fallen Princesses at times plays on specific objects of enchantment as a means of emphasizing the lack of fantastic fortune in its subjects’ lives. Goldstein’s photograph The Princess an the Pea addresses poverty by placing the folkloric princess with the fantastic ability to sense a single pea beneath twenty mattresses atop twenty mattresses in an urban junkyard, foregrounding a bulldozer. What role might sensitivity play in economic depression? Similarly, invokes Rapunzel’s themes of entrapment and isolation to address illness. In perhaps the most darkly compelling image of the series, the heroine with the impossibly long hair is transformed into a chemo-patient. Her gaze downcast, she sits on a hospital bed attached to an IV, a long braid in her hands. Both photos cleverly take fantastic images of folkloric enchantment – twenty mattresses stacked one on top of another, synthetic hair – and place them in plausible situations. The magnitude of the subjects’ misfortune is fantastic, but the technologies of their hardships are far from enchanted.

Enchantresses and Culpability

Perhaps no image of Fallen Princesses achieves the complexity of Not-So-Little Red Riding Hood, a reimagination which stuffs Little Red Riding Hood’s iconic basket full of burgers and fries. Red Riding Hood herself is shown as a plump young woman, strolling alone through a sunny forest while slurping a soft drink. When Goldstein posted selections of Fallen Princesses on the photography site JPG Mag in the spring of 2009, the photo drew commenter ire for reading as an easy fat joke, and continued to provoke fiery discussion on feminist blogs. Women’s Glib criticized it as containing, “two glaringly problematic stereotypes…that fat people eat indiscriminately and ‘unhealthily’; and that being fat is the ultimate downfall” (Women’s Glib 2009). Meanwhile, The Sister Project countered that the photo takes aim at, “the flawed society that we currently live in, where mainstream diets are made to poison consumers” (The Sister Project 2009). Is Red Riding Hood a culprit, deserving of blame and derision? (“Ha! She’s fat!”) Or is she a victim, in need of rescue and empathy? (“Fast Food is killing us!”) I argue that by inviting those two oppositional – and dangerously reductive – readings, Not So Little Red Riding Hood moves beyond them. By deploying twin impulses to shame women or pity them, might the photograph actually reveal its subject’s latent agency?

To understand how well equipped Red Riding Hood is in articulating such a conflict, we need only look to the history of the tale. Feminist anthropologist Yvonne Verdier documented how Red Riding Hood’s shift from oral tale to literary text (and, consequently, its transition from female to male authorship) was accompanied by the infantilization of its protagonist (Douglas 1995). Through fieldwork in rural France, Verdier uncovered a variation of the familiar tale that predates its seventeenth century sanitization by Charles Perrault. In the bawdy Verdier variation, the wolf eats the grandmother – and so does Red Riding Hood, albeit unwittingly. She performs a striptease for the wolf at his behest and then climbs into bed with him, where (yes) she can’t stop remarking on how big he is.

Sexual double entendre, however, is far from the most striking difference between this early iteration of the tale and its subsequent literary adaptations. This version of the tale, which Verdier describes as belonging to a tradition of female storytellers, does not end in the protagonist’s death (as in Perrualt’s text) nor with her rescue by a kindly woodcutter (as in the Brothers’ Grimm). Instead, Red Riding Hood escapes through her own wiles. She tricks the wolf by asking him to tie a leash around her while she relieves herself outside, but instead ties her end of the leash to a tree, and escapes.

In contrast, the textual variations by Perrault and the Grimms drain the tale of its bawdy playfulness and feminist resourcefulness alike. As the anthropologist Mary Douglas has argued, they suggest a much younger protagonist (Douglas 1995), and, according to folklorist Jack Zipes, they force her to bare responsibility for the wolf’s assault. Significantly, in Zipes’ examination of the illustrations that accompany the story’s printed tradition, he places special emphasis on Red Riding Hood’s woodsy encounter with the wolf. His exhaustive study reveals the scene’s depiction in nearly every illustrated version of the tale ever printed (Zipes 1987). Beginning with Gustave Doré’s 1862 illustration, originally designed for Perrrault’s fairytale collection and reprinted in multiple anthologies thereafter, these depictions mark the woods as a space where society’s rules are broken and a young girl can do the forbidden. Significantly, in the woods, she does not merely talk to the wolf, she nearly touches him. The little girl’s proximity to the wolf in the Doré illustration makes their encounter look something like a dance. Writes Zipes of the illustration:

Little Red Riding Hood appears to invite the wolf’s gaze/desire and therefore incriminates herself in his act. Implicit in her gaze is that she may be leading him on – to granny’s house, to a bed, to be dominated. (Zipes 1987, 243)

The wolf may be big and bad, but this illustration sets Little Red Riding Hood up: the ensuing tale will be about her punishment. But what is her crime? She talks to the wolf, yes, but does doing so make her stupid or sultry?

As Zipes demonstrates, Victorian illustrators damn her as both: they make her coy. An 1870 illustration by Walter Crane shows a Little Red Riding Hood cocking her hip while hearing out the Wolf, one foot placed forward so that the front of her cloak falls open, revealing her teenage body underneath. An 1880 illustration from Father Tuck’s Fairy Tale series makes Little Red Riding Hood younger, but no less coquettish. (Zipes 1987). In the Father Tuck illustration, the little girl is drawn face forward, equal in size to a dapper wolf adorned with a monocle and top hat, like a predatory Mr. Peanut. For her part, Little Red Riding lolls wide eyes in the wolf’s direction, one finger placed suggestively in her mouth.

At this point, it should come as no surprise that Little Red Riding Hood is often discussed by folklorists as a prototypical rape fantasy. Diane Herman (Herman 1979), Susan Brownmiller (Brownmiller 1975) and others have identified rape culture as stemming from a dangerous understanding of heterosexual sex wherein women passively await male acts of sexual aggression. These Victorian Red Riding Hood illustrations suggest how deeply rooted such cultural assumptions may be. The seductive innocence with which these protagonists are drawn, however, bears little resemblance to the craftiness of their feminist forbearer in the Verdier version. They suggest the subversion of feminine ingenuity with a darker matrix of enchantment: the intersection of male predatory instincts and female collusion. Through her encounter with the wolf, Red Riding Hood transforms from a naughty child to a wanton young women; the wolf from untouchable forest animal to knowable predator. The process of enchantment in the fairy tale is activated not merely by the wolf’s anthropomorphism, but by its collusion with budding (and punishable) feminine sexuality.

Interestingly, by the mid-twentieth century, illustrators neutered the sex appeal of both the wolf and Little Red Riding Hood alike. A 1968 illustration reminiscent of the Father Tuck’s (Zipes 1987) keeps the wolf in a top hat, but transforms it from a marker of society to a shiny, curling cartoon that seems to mock its wearer. The upright wolf’s bare chest, meanwhile, is covered in a cloak of his own. At a great distance from the wolf walks Little Red Riding Hood, diminutive as a pixie. Her head is big; her body small. She looks like kewpie doll.

During the same time period, images of adult Little Red Riding Hoods turned explicitly sexual. In the 1950’s, Max Factor’s “Riding Hood Red” lipstick bore the slogan “to bring the wolves out.” A 1953 ad for the lipstick in the magazine Vogue featured a sexy, red cloaked woman and the copy, “turn the most innocent look into a tantalizing invitation.” (Zipes 1987). If the Victorian era saw both women and girls as coquettish innocents wanting male domination, these illustrations indicate a twentieth century rift: girlish pixies grow into femme fatales, who knowingly wield their sexuality to seduce otherwise powerful men. Here, the positive connotations of folkloric enchantment see a dark flip side in the role of the female enchantress, a seductress who compels powerless men to pursue her.

Bearing in mind last spring’s two fairytale-focused hits – Orenstein’s book Cinderalla Ate My Daughter and Catherine Hardwicke’s movie Red Riding Hood – we can see Red Riding Hood’s virgin/whore duality playing out in the present day, in the pastel princess attire peddled at preschoolers and in the proverbial vampires and big bad wolves framed for teenagers as model lovers. What happens when contemporary grown women overcome the seductive, punishing promise of bad boy beasts? What happens after Twilight?

Body Politics

It would be easy to argue that, as the industrial commodification of fairy tales replaces the complex technologies of enchantment with superficial, mass produced magic wands and other princess gear, tales themselves will lose the enchanting power which Bettleheim finds so essential to social education. However, the publisher-selected illustrations of Red Riding Hood which Zipes critiques are as much a tool of industry as contemporary Disney princess gear, and the very proliferation of fairytale iconography suggests that the lessons of enchantment are perhaps shifting, rather than vanishing altogether. With Fallen Princesses, Goldstein participates the shift not merely by quoting the precedents of enchantment, but by literally altering the landscapes of the tales.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Goldstein’s Fallen Princesses is what the series lacks. Though the series depicts a host of serious issues faced by women today, including illness (Rapunzel), poverty (The Princess and the Pea), war (Jasmine), and isolation (Pocahontas), sexual violence is inconspicuously absent. Further, where men are included in the series, they are explicitly marked by passivity. Cinder puts Cinderella alone at a dive bar, in a ball gown, an up-do, and long white gloves among men in denim and boots. Although the bar is filled exclusively by men, they slouch in their seats beside their drinks and she appears wholly unthreatened by their presence. No cues are given to their danger, or even their sex appeal. Likewise, the elderly dejection of Beauty’s would-be suitor renders him passive, even with a passed out woman by his side. Similarly Snowy, the only series to feature a younger and potentially virile young man, takes care to mark his passivity in the face of his wife’s industriousness. Although I am not suggesting that sexual assault is not a serious contemporary issue, to what extent might Fallen Princesses suggest that, three centuries after Perrault published Tales of Mother Goose and three decades after Brownmiller published Against Our Will, fear of violent aggression need not make a top ten list of Western women’s concerns? At the very least, it doesn’t make Goldstein’s.

Although I would like to argue that the controversial photograph Not-So-Little Red Riding Hood marks a departure from the illustration’s genesis in female sinfulness, I can’t do that without deploying the underlying assumption that this story is a little girl’s. In reality, it ceased to be a girl’s story as soon as the versions by Perrault and the Grimm’s began circulating. As Zipes argues of the Victorian illustrations of Red Riding Hood’s initial encounter with the wolf, she isn’t a little girl so much as she is a fantasy of femininity, one used as a justification for its subordination. Tellingly, Zipes wrote in 1986:

Ultimately, the male phantasies of Perrault and the Brothers Grimm can be traced to their socially induced desire and need for control – control of women, control of their own sexual labido, control of their fear of women and loss of virility. That their controlling interests are still reinforced and influential through variant texts and illustrations of Little Red Riding Hood in society today is an indication that we are still witnessing an antagonistic struggle of the sexes in all forms of socialization, in which men are still trying to dominate women. [Zipes 1986, 257]

A quarter century later, are men still engaged in the fraught struggle for domination that Zipes describes? Fallen Princesses answers that question with a quiet, “who cares?” In the storied scene of Little Red Riding Hood in the woods, Goldstein craftily erases the male presence entirely, and instead shifts the story’s burden of control to its female protagonist.

Disordered eating, as Gillian Brown has argued, is fundamentally died to humanist notions of bodily control (Brown 1991); by stuffing Red Riding Hood’s basket with sodas and fries, Goldstein harnesses the aggressive struggle for control that forms the basis of the story. And in a subtle, brilliant twist, that struggle is not about men attempting to master their baser urges while also mastering the so-called fairer sex, but about a woman’s struggle to gain control over her own body. This Red Riding Hood is the body in question, and her body is meant to attract our attention, much as Victorian illustrators meant her body to attract the attention of the wolf. As in all internal struggles for a Foucaultian semblance of control, Red Riding Hood is both disciplinarian and disciplined, subject and object both.

Just a Little Bit Naughty

Shortly before Shortly before Goldstein began developing Fallen Princesses, an advertising team in Australia began looking for a new way to market low fat flavored milk. The ensuing fairytale-themed ad campaign bears the slogan, “just a little naughty.” Each print ad features the same model, dressed in fairytale attire against a white background. As Rapunzel, she demonstrates her naughtiness by cutting off her long braid. As Cinderella, she wears a patent leather boot in place of a glass slipper. There is no real narrative intervention, however, for the ad’s take on Red Riding Hood, so solidified is Red Riding Hood’s cultural her role as femme fatale. The wolf tattoo which the ad places on her exposed forearm is actually in keeping with traditional depictions of this prototypical misbehaving girl.

With Little Red Riding Hood already a signifier of naughtiness, to what new low can Fallen Princesses sink her? Snow White, in place of a royal kingdom, gets an unhappily suburban ever after. Cinderella, in place of a royal kingdom, gets a skeevie dive bar. The heroine of The Princess and the Pea, in place of a royal kingdom, gets a pile of junkyard mattresses. And Red Riding Hood, in place of digestion by a wolf, gets to eat hamburgers and fries.

In her own critique of Little Red Riding Hood, Mary Douglas suggests an anthropological approach to folklore would do well to examine not how humorous a story is, which Douglas sees as a subjective assessment, but how light the tale is meant to be. This photograph – from its to its punning title to the fact that its protagonist’s clogs look a little like crocks – indicates a lightness of spirit, a winking whimsy. Further, it is literally a light photograph. The studio lighting sets Red Riding aglow, making her pop against the woodsy background. Does that lightness poke fun at its protagonist’s fat body (a potentially mean spirited gesture, to be sure) or does it make a pointed comment about the surreptitiously sinister realities of fast food? Goldstein marks the photograph as light, while viewer perspective interpolates Red Riding Hood as an object of either scorn or of pity.

Significantly, scorn and pity are, historically, attitudes with which society has addressed the proverbial fallen women from whom Goldstein takes her title. Goldstein not only simultaneously solicits both scorn and pity from her audience, she does so by erasing the threatening male presence from the much-depicted scene. In doing so, she places the story’s emphasis back on Little Red Riding Hood. Not-So-Little Red Riding Hood thus works to undo the titular heroine’s objectification, by making it Little Red Riding Hood who struggles with control, and by positioning control as hers for the taking. Goldstein’s series promises a look at fallen heroines; Not-So-Little Red Riding Hood suggests a potential for the fallen to rise again.

Li Cornfeld is pursing a PhD in the Department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill University.

Works Cited

Bettleheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. (New York, NY: Vintage, 1975.)

Brown, Gillian. “Anorexia, feminism, humanism.” Yale Journal of Criticism. 5(1):189-215.

Brownmiller, Susan. 1991. Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1975).

Douglas, Mary. 1995. “Red Riding Hood: An Interpretation From Anthropology.” Folklore 104(1-7).

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Trans: Jack Zipes. (New York: Bantam, 2003).

Herman, Dianne. “The Rape Culture.” In Women: A Feminist Perspective edited by Freeman. (Palo Alto , CA : Mayfield, 1979).

Perrault, Charles. The Complete Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault. Trans. Neil Philip. (New York, NY: Clarion, 1993.)

The Sister Project; “Fallen Princesses:’ Damsels in a Different Kind of Distress,”” blog entry by Anastasia Smith http://thesisterproject.com/smith/fallen-princesses-damsels-in-a-different-kind-of-distress/. June 24, 2009.

Women’s Glib; “Princess Fat Shaming,” blog entry by Miranda Mammen.http://womensglib.wordpress.com/2009/06/19/princess-fat-shaming/. June 19, 2009.

Zipes, Jack. “A Second Gaze at Little Red Riding Hood’s Trials and Tribulations.” In Don’t Bet on the Prince: Contemporary Feminist Fairy Tales in North America and England, edited by Jack Zipes, 227-260. New York, NY: Routledge, 1987.

Princesses and perspective: Feminist perspectives by incongruity in Dina Goldstein’s Fallen Princesses

Presented at the National Communication Association Convention in Washington, D.C. Nov. 24, 2013

Sarah T. Partlow Lefevre, Ph.D.

Professor, James E. Rogers Department of Communication, Media, and Persuasion Idaho State University

[email protected]

1 © Sarah T. Partlow Lefevre. All Rights Reserved. Please do not cite or duplicate without permission.

Princesses and Perspective

Introduction

Dina Goldstein is a photographer living in Vancouver, Canada. In 2007, her three year old daughter was embracing princesses. At the same time her mother learned she had breast cancer. The juxtaposition of these events lead Goldstein to experience a moment of discord or what Kenneth Burke would term a moment of incongruity. Goldstein’s (2011a) mother’s cancer diagnosis and her daughter’s “princess phase” created a stark sense of juxtaposition between the difficulties of real life and the imaginary, perfect world of the princess (p. 31). She said, “The two events collided and made me wonder what a princess would look like if she had to battle a disease, struggle financially or deal with aging” (p. 31). As Goldstein (2011b) pursued the idea, she “began to imagine Disney’s perfect princesses juxtaposed with real issues that were affecting women . . . such as illness, addiction, and self-image issues” (pp. 36-37). From this dissonance, Goldstein’s photographic series Fallen Princesses was born. The series includes ten pictures featuring princesses including the characters of Snow White, Cinderella, Rapunzel, Jasmine, the Little Mermaid, Pocahontas, Red Riding Hood, the Princess and the Pea, Belle, and Sleeping Beauty. In preparation for this essay, I examined seven of the images that are representative of Disney princesses. Each of the Disneyesque princesses is inserted into a situation that reflects or exaggerates the imperfections of reality. Goldstein explained, “In my scenarios they are symbols of fantasy placed in a vision of dark reality” (p. 38). The series juxtaposes the fantastic and utopian nature of the princess with dark depictions of real life.

Since the images were first circulated online in 2009, they have gone viral three times (Ghert- Zand, 2013; Odell, 2013). According to Hyslop (2009a), “when Goldstein’s Fallen Princess collection hit the Internet . . . it created a buzz that quickly went global, capturing the attention of bloggers and journalists from the U.K. to Mexico” (F12). As I write the final draft of this essay in 2013, Goldstein’s images have again gone viral (Ghert-Zand, 2013; Odell, 2013). The Inquisitr (2013) notes, “Photographs from the series are being shared all over the internet with Facebook and Twitter users raving about the unique take on Disney’s most popular princesses” (Inquisitr, 2013). Initially, in 2009, Goldstein was “blindsided” by the “ferocity of the debate” (Hyslop, 2009, p. D13). At the time she said, “It’s all been a bit overwhelming” as “her Fallen Princess collection . . . incited thousands of bloggers to flex their digits and worldwide journalists to request interviews” (Hylsop, 2009, p. D13). As the images have been shared around the world, the debate and discussion about the images made it clear that “folkloric tropes have near universal relevance – but not universal interpretation” (Cornfeld, 2011, p. 17). It is true that the images have provoked discussion on a massive scale. Thousands of people have commented on the images expressing a range of responses from disgust to adoration. Such responses rely on the audience’s different understandings of what the photographs mean. Goldstein (2011c) said, “I’m finding that there are many interpretations of my work and that’s fine. Art is meant to elicit discussion and debate” (Goldstein, 2011c p. 40) and, “I like the fact that my work is creating dialogue and I knew that the subjects would resonate with women especially, but I never intended to offend or disparage anyone” (Hyslop, 2009, p. D13). Positive or negative, Goldstein’s Fallen Princesses struck a chord with worldwide audiences several times. But, why?

I suggest that the Fallen Princesses series performs significant cultural work by problematizing princess culture in a variety of ways. Such images create incongruity by using shifts in depictions of race, class, and gendered appearances of princes and princesses. By juxtaposing idealized notions of Disney type princesses with negative representations; these pictures create feminist perspectives through incongruities. Enjoyed by a broad cross section of the population, such images jar the audience into considering worlds beyond those idealized by Disney and princess culture. I use Burke’s theory of perspective by incongruity to examine the photographs featuring Disney-like princesses. In this essay I discuss the following photos: Snowy, Jasmine, Rapunzel, and Belle. Issues of race, class and gender are juxtaposed in these images. By identifying the visual rhetorical strategies present in these conflicts between idealizations in fairy tales and dark imaginings of reality, this essay pinpoints multiple interpretations and the ways that those understandings push the audience to accept feminist principles. Feminist perspective by incongruity may help explain how these conflicting messages elicited strong responses from both fairy tale fans and critics. Such insight can expose how this series gains wide acceptance while engaging in somewhat caustic social criticism. In particular, a feminist Burkean analysis allows exploration of the ways that these incongruities crack open multiple and contradictory meanings within a text and how these meanings function for different audiences. I first discuss the cultural import and iconic status of Disney princesses. I then discuss and define Kenneth Burke’s notion of perspective by incongruity in the context of feminist criticism. Finally, I examine Goldstein’s photographs as they exhibit perspective by incongruity.

Disney Princesses as Cultural Icons

Disney princesses are enmeshed in and have significant effects on our culture. Not only are they the primary link between modern society and mass exposure to fairy tales, they are ever present commercial and cultural icons. Disney icons present stories in a flat rather than dynamic way that glorifies utopian outcomes with no reference to reality. For critics, this is cause for concern. Initially, it is well recognized that Disney dominates the telling and distribution of fairy tales in contemporary society (Do Rozario, 2004; Sweeney, 2011; Zipes, 1995). Zipes (1995) suggested that Disney has cornered the market on contemporary understanding of fairy tales. He wrote,

If children think of great classical fairy tales today . . . they will think Walt Disney. Their first and perhaps lasting impressions of these tales will have emanated from a Disney film, book, or artifact . . . . Disney managed to gain a cultural stranglehold on the fairy tale. (p. 21)

Indeed, an array of fairy tale representations have been remade in Disney style including as Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Beauty and the Beast, Rapunzel, Snow White, The Little Mermaid, and others. Do Rozario (2004) argued that “the Disney princess [is] in effect the ‘princess of all princesses’ ” (p. 34). The Princess is ever present. Do Rozario (2004) noted that she is a “fairytale staple” present in “even the world’s republics” (p. 34). The influence of Disney princesses is enduring and global.

In addition to being the primary factor in the retelling of fairy tales, Disney princesses are commercial icons based on archetypal characters. Disney princesses are so deeply ingrained in the culture that they are icons for many people. Bostdorff (1987) defined icon as “as any image that represents enduring attitudes, values, or beliefs of a particular society. An icon is considered sacred by most citizens, and it encompasses . . . ideals” (p. 50). Iconic representations gain their power because they “symbolize treasured values and beliefs” (p. 52). This is also true of many people’s reaction to Disney princesses. Sweeny (2011) argued that Disney has taken the princess archetype from the films and installed it in all aspects of our consumer lives. Sweeney wrote,

Disney . . . has repeatedly demonstrated the enduring power and prestige of the princess archetype . . . . Disney’s Princess films . . . continue to remain popular, in part because . . . The trademarked Princesses . . . are not simply characters in films but painted faces on sippy cups and backpacks, flesh-and-blood creatures at theme parks, and the subjects of their own websites . . . they are literally almost everywhere. (p. 66)

Part of the popularity of the commercial archetype is its promise of transformation and its ability to tease the audience with the elusive notion of perfection and the world of happily ever after that welcomes Disney princesses. Sweeney (2011) described the way that the princess archetype makes this promise to women and girls of all ages. She wrote,

The idea is that the princess archetype . . . offers the possibility of romance and transformation for females of all ages. Most notable, perhaps, is the variety of wedding options Disney offers to grown-up Princess enthusiasts, including wedding rides in Cinderella’s coach and designer wedding gowns that echoes those of the Princesses . . . by playing a grown-up game of dress-up—a consumer can literally transform herself into something worthy of a Disney dreamscape” (Sweeney, 2011, p.70)

This promise of transformation into something magical arises from the very simplicity of the stories themselves which encourage too easy interpretations of the world. Zipes (1995) explained “The diversion of the Disney fairy tale is geared toward non reflective viewing. Everything is on the surface, one-dimensional, and we are to delight in one-dimensional portrayal and thinking, for it is adorable, easy and comforting in its simplicity” (p. 40). This one dimensionality or flatness of the story presentation is captivating precisely because it strips out the messiness of real life. Zipes (1995) argued, “The great ‘magic’ of the Disney spell in that he animated the fairy tale only to transfix audiences and divert their potential utopian dreams and hopes through false promises of the images has cast upon the screen” (p. 22). Engaging such utopian fantasies solidifies the audience’s allegiance to the icon of theDisney princess.

One internet search for Disney fan art confirms that there are thousands of drawings and re- drawings of the beloved Disney princesses. The fantastical notion of happiness and success conveyed through these fairy tales and Disney in particular leaves cause for concern. Zipes (2011) argued that the version of happiness forwarded through the culture is totally unrealistic and must be challenged. He wrote, “The fairy tale notion about happiness must be radically turned on its head if we are to glimpse the myths of happiness perpetuated by the canonical fairy tales and culture industry and to determine what happiness means” (Zipes, 2011, p. 15). Dina Goldstein’s Fallen Princesses radically challenges utopic visions of princess culture. Zipes (2011b) praised the photos for their “biting commentary” and the “dramatic way” they revealed “the contradictions of the classical tales” (p. 83). Exposing these contradictions allows individuals in society to reconcile their utopian ideals of the princess archetype with their experiences in their daily lives. Zipes (2011) wrote, “The fallen princesses in her photos . . . seek to come to terms with social conditions that limit our ability to recognize the myths of happiness . . . Goldstein hopes that we may alter our vision” (p. 6). This altered vision, Zipes (2011) contended would allow individuals to recognize the “dazzling false promises” rather than being blinded by them (p. 16). This “de-disneyfing” that Zipes (2011) identified resonated globally (p.15). Zipes noted that “they have received global attention as artworks that comment critically on the Disney world and raise many questions about the lives that women are expected to lead and the actual lives that they lead” (Zipes, 2011, p. 15). Goldstein’s series is effective because it challenges one-dimensional representations of fairy tales and Disney princesses in particular. Such a challenge opens space for individuals consuming these images to reflect in a multi-dimensional way. Zipes (2011) wrote, “her photos imply that women(and men as well) must be on the alert in the society of spectacle not to believe the images imposed on us, but to create our own narratives and representations” (p. 16). Zipes is correct in his assessment of the effect of the photos. They do cause people to reassess and step back from uncritically embracing iconic Disney princesses. In this essay, I extend Zipe’s analysis using Kenneth Burke’s concept of perspective by incongruity. I argue that the incongruous nature the photos creates symbolic cracks and fissures in the princess icon. As these fissures spread in the minds of viewers, many experience a moment of feminist perspective by incongruity. Feminist perspective by incongruity is not a matter of telling true stories in the place of false ones. Instead, it is about a process of opening discussion, creating a response, and promoting feminist insight. To complete this approach, I first delineate Burke’s theory of perspective by incongruity and articulate feminist perspective by incongruity as oneexpression of Burke’s method. I then examine the photos in this context to understand messages the images send, their incongruities, and ultimately their feminist perspectives.

Kenneth Burke’s Perspective by Incongruity

Kenneth Burke (1984) argued that humans have orientations which are particular symbolic outlooks on the world in which we live. An orientation is simply a “way of viewing the world” (Blankenship, Murphy, & Rosenwasser, 1974, p. 4). Burke, wrote, “An orientation is a largely self- perpetuating system, in which each part tends to corroborate the other parts. Even when one attempts to criticize the structure, one must leave some parts of it intact in order to have a point of reference for his criticism” (p. 169). Pieties maintain a sense of order in an orientation (George & Selzer, p. 130). Rosteck and Leff (1989) argued, “Piety thus functions to sustain the coherence of a perspective, but it now attaches itself to all levels of human experience” (p. 327-328). In other words, humans desire to explain the world consistently, in a way that minimizes symbolic disruptions. Burke argued that humans seek perfection within their symbolic systems. This drive for perfection or entelechialization is the all too human “tragic tendency to push toward perfection regardless of the consequences” (Renegar & Dionisopoulos, 2011, p. 327). Hubbard (1998) wrote,“Entelechy drives people toward the logical ends of their rhetoric and behavior. Entelechy, or the drive toward perfection, results from our ability to use symbols to envision the extreme ends of behavior” (p. 360). In this sense, humans become rotten with perfection because they extend their symbols systems to extremity (Burke, 1966). Individuals who adhere to a particular orientation may have trouble seeing outside that approach. He wrote, “The universe would appear to be something like a cheese; it can be sliced in an infinite number of ways—and when one has chosen his own pattern of slicing, he finds that other men’s [sic] cuts fall at the wrong places” (Burke, 1984, p. 103). The comparison to slicing cheese illustrates the human desire to maintain and perfect particular symbolic patterns. Humans prefer their own organization and seek to perfect that organization at the expense of validating others’ approaches.

Applied in the context of human orientations, the principle of perfection might mean pieties are used to perfect and extend a system until it becomes excessively rotten or extends perfection into rottenness. To prevent such excess, Burk suggested a comic corrective or an embracing of imperfection. Burke wrote, “The ultimate result is the need of a reorientation, a direct attempt to force the critical structure by shifts of perspective” (Burke, 1984, p. 169). Forcing new perspectives works where argument cannot because humans tend to cling to their symbolic orientations. Humans have great difficulty questioning their deeply held beliefs. Rockler (2002) wrote, “Traditional logic often is not an effective tool . . . because people often . . . refuse to question deeply held cultural assumptions. To persuade people to question their pieties, a rhetor needs to adapt a more complicated strategy”(p. 18). Perspective by incongruity is one way to challenge such deeply held assumptions and to provide a comic corrective. Perspective by incongruity requires the juxtaposition of unlike symbols. The dissonance created through symbolic clash can lead people to challenge deeply held assumptions. Burke (1984) provided a typical example of this type of discordant combination, The gargoyles of the Middle Ages were typical instances of planned incongruity. The maker of gargoyles who put man’s-head on bird-body was offering combinations that were completely rational as judged by his logic of essences. In violating one character of classification, he was stressing another. (p. 112)

The result of incongruity is delinking established symbolic relationships and breaking them into multiple pieces. Burke (1984) compared it to “wrenching apart . . . molecular combinations” and exposing symbols “to the same ‘cracking’ process that chemists now use in their refining of oil” (p. 119). Burke (1984) suggested, “One should establish perspective by looking through the reverse end of his glass, converting mastodons into microbes, or human beings into vermin upon the face of the earth” (p. 120).

Such juxtaposition directly confronts humans’ previously established symbolic orientations. Bostdorff (1987) noted,“Perspective by incongruity involves altering an orientation or expectation by viewing incongruity, which is inconsistent or not in agreement” (p. 44). Viewing inconsistent symbols in concert pushes the audience to reconsider their pieties. It works because it forces otherwise unlikely comparisons. According to Blankeship, Murphy, & Rosenwasser (1974), “It deliberately wrenches loose a word belonging customarily to a certain category and applies it to a different category” (p. 3). Perspective by incongruity is effective because it breaks down previously unbreakable symbolic systems. As Blakesley (1999) suggested, “Perspective by incongruity . . . cracks disciplinary codes and helps us construct new patterns of experience and new ways of relating to them” (p. 83). Indeed, it forces the audience, to incorporate uncertainty in their perspectives. Waisanen (2009) explained, that such dissonance can “continually force us to see these issues from more than one angle, creating shocks of insight” (p. 135). Gusfield (1989a) wrote that perspective by incongruity “is an exhortation to see the limited nature of any one cognitive framework” (p. 44). Perspective by incongruity can challenge single orientations and allow humans to understand a “multiplicity of possibilities” (Gusfield, 1989a, p. 44). Thus, perspective by incongruity can spark multiple symbolic understandings.

Perspective by incongruity induced insights are effective in challenging calcified orientations because they enhance argumentative effectiveness, suggest new symbolic linkages, and encourage production of new vocabularies and perspectives. Strategies employing perspective by incongruity draw attention and starkly illustrate arguments. Waisanen (2009) wrote, “These comic strategies of incongruity are rhetorical ways togenerate attention, heightening and amplifying arguments” (p. 135). In addition, such strategies encourage the audience to examine both similarities and differences between the incongruous symbols. Renegar & Dionisopoulus (2011) argued, “Juxtaposing two incongruous ideas can alter an orientation . . . and allow new perspectives to flourish as unnoticed similarities may emerge between elements previously viewed as incongruous” (p. 332). Dissonance in this form is productive. Incongruity produces multiple perspectives challenges single vocabularies and encouraging a level of comfort with ambiguity. Burke (1984) wrote, “One sees perspectives beyond the structure of a given vocabulary when the structure is no longer firm” (p. 117).

Incongruities in symbolic understandings produce “a fragmentary body of interpretations— tentative, experimental, sometimes felicitously heuristic” (p. 307). When interpretations are fragmentary and in conflict, dialogue ensues. Bridges Watts (2007) wrote,

On one level, these forces act in opposite ways on the situation. On another level, however, the simultaneous working of these opposing forces results in the development of the community through dialogue or juxtaposition of the two views brought together by their opposition to one another. The social forces of tradition-upholding/change- questioning and tradition-questioning/change-promoting indeed move in opposite directions, as do centrifugal and centripetal motion. But at the same time. These forces are juxtaposed or combined within the same community, and they thus work together, perhaps in spite of themselves, to create something greater than either force in itself: the exchange of ideas, which enhances the community through the conflicts of its various factions. (p. 168)

Indeed, the dialectic nature of perspective by incongruity makes it a powerful tool. The debate and

discussion that results from perspective by incongruity is an essential part of the process. Dialogue draws people into a productive exchange of ideas. In this way, perspective by incongruity “is the wedge that pries apart established linkages. Yet, at the same time, it prepares for new fusion” (Rosteck and Leff, 1989, p. 330). By moving beyond established symbolic representations, perspective by incongruity allows insights beyond the limits of the original symbol system. In a sense, it allows the unknown to become known. Rosteck & Leff (1989) recognized that perspective by incongruity revolutionizes all types of symbols. They wrote, “Perspective by incongruity aligns and reorders entire domains of experience not just word meanings” (p. 331). In this way, audiences may obtain “an additional angle from which to see reality” and be able to “overcome the particular blindness of our accustomed usages” (Gusfield, 1989b, p. 23). Perspective by incongruity is a nifty tool that can be used in an almost infinite number of situations.

Burke (1984) recognized its exponential applications. He wrote, “‘Perspective by incongruity’ . . . turns out to have been a kind of methodological Pandora’s box” (p. 306). One area where perspective by incongruity has been repeatedly employed is social activism (Demo, 2000; Dow, 1994; Dubriwny, 2005; Foss, 1979; Gusfield, 1989a; Rockler, 2002; Young, 2010). Insights gleaned through perspective by incongruity are often social or cultural in nature. Levasseur (1993) wrote, “These arguments could create ‘new meanings’ for old phenomena, and such new meanings could cause society to re-examine and question its existing orientation” (p. 203). Foss (1979) recognized the potential of perspective by incongruity to promote social change. She wrote, “This technique is common in rhetorical situations where a communicator attempts to supplant a traditional view . . . with a new and restructured one” (p. 11). In this way, rhetors might “shatter the world created by traditional rhetoric” (p. 13). This approach works because it causes people to reconsider long held assumptions. New perspective might substitute for old ones making perspective by incongruity a tool to replace “an old reality with a new one” (p. 14). In theory, this type of symbolic disruption should work regardless of the particular movement for social change. In the next section, I discuss the use of Burke’s theories in a feminist context. In particular, I argue that perspective by incongruity can be an effective method for promoting feminist ideas.

Feminist Perspectives by Incongruity

Feminists have debated whether to adopt Burke’s methods and theoretical approaches in critical analysis and in movements for social change. However, Japp (1999) argued that the feminists should see Burke’s approach as an open system that “can be reoriented to new sociopolitical environments” (p. 114). Viewing Burke’s system as open means that useful parts of his approach should be adopted and the rest can discarded by feminist theorists. Japp (1999) wrote, “While some concepts within the Burkean system may be reclaimed for women’s experience, there may well be those that are not. Each concept must be critically assessed for its potential utility” (p. 128). Despite her discomfort with some aspects of Burke’s theories, Japp (1999) recognized their positive impact on her world. She wrote, Burkean methods “allowed me to explain, subvert, and even at times influence my world” (p. 113). Because of personal experience Japp (1999) argued that Burke theorized feminist “survival tactics” (p. 113). She wrote,

My conviction that Burke contains much that is relevant for feminist scholarship is shaped, in part, by personal experience. Certainly I encounter passages that seem alien to my experience of the world and engage concepts that fail to include my perspectives, yet I have found in Burke an indispensable array of guerilla tactics for survival in a field of masculinist symbols. (p. 113)

Using the metaphor of guerilla symbolic tactics allows feminist to assess individual theories for their potential utility. Additionally, Japp (1999) recognized the power of Burke’s system to create social change. She suggested, “His critical system was directed toward unsettling dominant and dominating structures and practices” (p, 116). Thus, feminists can and should use Burke’s theories to promote social change. Japp (1999) wrote, “reclamation of Burke must not only provide strategies for personal survival; it must emphasize the power of Burke’s system in the struggles for societal change” (Japp, 1999, p. 129). One Burkean method that has particular resonance for feminist activism and theorizing is perspective by incongruity.

Feminist perspective by incongruity is a powerful method because it questions and exposes dominant ideologies, it serves a consciousness raising function, it allows individuals to question and transform their identities, and it produces new vocabularies and reclassifies the world. Initially, feminist perspective by incongruity challenges dominant symbol systems. Foss (1979) wrote, “A jarring opposing image is introduced that forces the auditor or reader to re-think and question — at least momentarily – the components of his or her world” (p. 13). Incongruities expose the deficits of the dominant ideological system. Young (2010) elucidated, “Scholars can utilize perspective by incongruity as technique for interrogating intersections of image and words that expose dominant ideologies ofgender, sexuality and consumerism” (Young, 2010, p. 90). As a method, feminist perspective by incongruity can promote social change without revolution. It fights against “monistic thinking that fails to reveal the limits of a single . . . experience [of] reality” (Gusfield, 1989b, p. 23). Indeed, it asks communicators “to see the limited nature of any one cognitive framework” (Gusfield, 1989b, p. 23). From a feminist perspective this ability to question modes of thought is indispensable. Demo (2000) explained, “The machinery of perspective by incongruity and the comic frame, then, engenders a form of social criticism that seeks to correct the inadequacies of the present social order through demystification rather than revolution” (p. 135). Thus, feminist perspective by incongruity challenges calcified ideologies that promote domination. It symbolically cracks dominant ideologies open and subjects them to further consideration.

It is in this process of consideration that perspective by incongruity promotes feminist consciousness raising. Dubriwny (2005) identifies perspective by incongruity as one method of consciousness raising that “can play a key role in reshaping of the meaning of individuals’ experiences, for it is through confronting moments of incongruity that people reevaluate their experiences” (p. 398).

Indeed, perspective by incongruity is inherently a consciousness raising mechanism. Demo (2000) wrote, “The comic frame hinges on the ambivalence engendered by incongruities. The comic frame privileges audiences by providing a unique vantage point from which to see the inaccuracies of the situation-creating what Burke labels ‘maximum consciousness’” (p. 134). Consciousness raising is important because it is “the primary means through which oppressed audiences are empowered and persuaded is the validation of their lived experiences” (Dubriwny, 2005, p. 400). Feminist perspective by incongruity is consciousness raising because it consistently transforms symbolic interpretations individually and collectively. Consciousness raising through feminist perspective by incongruity functions similarly to Dubriwny’s (2005) notion of collective rhetoric. She explained the transformative nature of collective rhetoric. She wrote,

The collective participation of individuals in the creation of an always-transforming text in this case contributes to a process of commemoration and public memory, and, in a similar fashion, I contend that the audience participation in rhetorical acts shapes the meaning of the messages through inclusion of many voices and the often diverse stories that such voices repeatedly tell. (Dubriwny, 2005, p. 399)

She elaborated, “A theory of collective rhetoric transforms audiences into active participants. The participation of multiple voices is a key to a variety of rhetorical processes” (Dubriwny, 2005, p. 399). As feminist perspective by incongruity jars audiences into questioning it also motivates them to participate in dialogue. The cumulative effect of feminist perspective by incongruity is collective consciousness raising. The consciousness raising effect is heightened in the era of new media where audiences are more participatory than ever before.

In the process of consciousness raising, feminist perspective by incongruity asks individuals to question their identities. Dow (1994) argued, “perspective by incongruity can do more than test audience assumptions about their external world; it also can question fundamentally their identity in relation to that world” (p. 229). Questioning one’s symbolic orientation and therefore identity is a necessary prerequisite to any type of meaningful change. The ability to change is what, for Burke, makes perspective by incongruity a comic corrective. Dow (1994) wrote,

This is what makes perspective by incongruity a comic strategy for Burke; it assumes that we can learn from exposure to mistakes and that such information ultimately will benefit us. Such possibilities are even more important when an audience is being asked to revise elements of their identity as well as their attitudes toward institutions or issues [emphasis in original]. (p. 239)

So feminist perspective by incongruity asks communicators to consider symbolic components of their identities and to consider new definitions and change. Renegar & Dionisopoulos (2011) posited, “A comic posture is a powerful mechanism for creating self-reflection, but the conclusions of that reflection must be left to the individual. In fact, to dictate the acceptable outcome of a comic frame is antithetical to its entire notion” (p. 339). Inability to mandate outcomes requires communicators to engage in dialogue without agreement. Indeed, “Perspective by incongruity is integral to a comic perspective because it exposes those things that had been previously obscured by tradition or habit, thereby encouraging an individual to recognize a multiplicity of options for viewing a situation”(p. 333). In feminist perspective by incongruity, that situation may be the live experiences that influence one’sidentity. Such dialogue empowers the individual to actively choose a progressive symbolic approach to identity.

In addition to exposing dominant ideologies, raising consciousness often collectively, and empowering individuals to craft their identities, feminist perspective by incongruity can promote social change through dialogue-induced symbolic juxtaposition. Dow (1994) argued, “Perspective by incongruity questions or deconstructs accepted meanings or pieties through comparison, reclassification, and renaming” (p.229). Rather than merely deconstructing, feminist perspective by incongruity offers communicators the opportunity to create a new vocabulary to understand the world. Ciesielski (1999) wrote, one “can reconstruct, rather than simply accept or destroy, the pieties that define our sociocultural being” (p. 264). Feminist perspective by incongruity allows one to “redefine the

previously unbreachable objective “realities” around us and redistribute priorities to re-create a “user- friendly” social environment” (Ciesielski, 1999, p. 264). Indeed, feminist perspective by incongruity opens minds to the need for and possibility of social change. Rockler (2002) wrote, “Perspective by incongruity is powerful because, if successful, it jars people into new perceptions about the way reality can be constructed and may encourage people to question their pieties. Perspective by incongruity encourages people to reclassify their outlook on the social world” (p. 18).